Agreeable to the Association

- HistoricAnnapolis

- Sep 18, 2020

- 4 min read

In September 1770, more than a year into a partial economic shutdown, many Annapolitans were weary but still committed to seeing it through to an acceptable outcome. In the summer of 1769, Marylanders had joined other American colonists in a boycott of British imports taxed under the Townshend Acts. A local Committee of Inspection enforced the nonimportation association in Annapolis and Anne Arundel County, just as similar groups did elsewhere. Parliament repealed most of the duties in March 1770, but as a matter of principle, it kept the tax on tea in effect. As an opposing matter of principle, most colonies largely continued to uphold the collective boycott, but some communities began to loosen their trade restrictions. As spring rolled into summer and late summer began to hint at the approach of autumn, a satisfactory resolution of the lingering stalemate between the Mother Country and her obstinate American children seemed as elusive as ever.

Articles in the September 13, 1770 Maryland Gazette offered different perspectives on the situation. An August story from Marblehead, Massachusetts reported that town’s rejection of a shipment of pork from New York because New Yorkers “had broke their Non-Importation Agreement, and deserted their Sister Colonies, at a Time when they well knew that a Union was most necessary for obtaining the desired End.” The people of Marblehead would not “have any Connection or Commerce with any Inhabitant of said Colony, until they give Satisfaction to the Committee of Trade at Boston for their base Defection.”

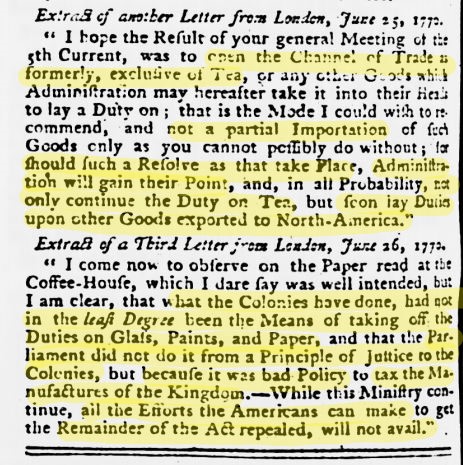

An August report out of New York conveyed the contents of two June letters from gentlemen in London. The first said that an “amazing Quantity of Goods … are daily shipping for Boston, Rhode-Island, Halifax and Canada,” as well as Virginia. The correspondent wrote that “the judicious Merchants of your Province, and those of Pennsylvania, … I am sorry to say have been duped by the other Provinces.” The second author wrote that he had personally seen a Philadelphia order for “upwards of 3000 l. Sterling Value, in Goods, without any Regard to the restricting Clauses.” If Philadelphia was jumping off the boycott bandwagon, gullible New York was being taken for a solo ride.

August news from Philadelphia quoted three London letters from June. The first writer said that Parliament’s incomplete reversal on the Townshend Duties “left us here in a Kind of Suspense, and turned our Eyes to the Conduct of the Americans.” Enemies of America predicted that even Bostonians would welcome British imports as the boycott agreement fell apart, but they were shocked when the ships returned with their cargoes still on board. English “Friends of America rejoiced openly over their Enemies” and hoped that Virginia shipments would also be rejected. If Americans only held firm, Parliament would surely repeal the tea tax in the coming winter.

The second letter offered advice to Philadelphia merchants, counseling them to open up trade to all imports except for tea. Holding a hard line would only provoke Parliament to “not only continue the Duty on Tea, but soon lay Duties upon other Goods exported to North-America.” The third letter asserted that American actions had little influence over Parliament. The colonial boycott hadn’t forced the partial repeal of the Townshend Duties, and Parliament hadn’t acted “from a Principle of Justice to the Colonies, but because it was bad Policy to tax the Manufactures of the Kingdom.” Americans were deluded if they thought their efforts would “get the Remainder of the Act repealed” as long as the current ministry was in power.

With such discouraging news reports and contradictory advice circulating, what was a Maryland mercantile firm to do? An advertisement by partners James Dick and Anthony Stewart demonstrates how one business coped in these unsettled times.

Dick and Stewart announced the recent arrival of imported goods “from London, in the Ship Betsey, Captain James Buchanan” which they now had “for sale at reasonable Rates, Wholesale and Retail, at their Stores in Annapolis and London Town.” Most importantly, they asserted that this “large Assortment of goods” was imported “agreeable to the Association,” meaning there was nothing among the cargo that violated the nonimportation agreement.

The partners had been investigated and reprimanded months before by the local Committee of Inspection (see my April 16 post on the Good Intent episode), and they had no desire for a repeat performance of that bit of unpleasantness. Undoubtedly, they hoped for an end to the boycott and a return to business as usual, but until that time came, they were prepared to keep their heads down and try to adhere to what were by now the not-so-new rules of trade. If they could make do selling plain fabrics, maritime basics, essential foodstuffs, and potent potables, they would. Let others, such as Thomas Williams and Company (see my June 11, July 30, August 6, August 13, and August 21 posts) attract the unwelcome attention of the Committee men. James Dick and Anthony Stewart would play it safe.

Read the September 13, 1770 issue of the Maryland Gazette starting here: https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc4800/sc4872/001281/html/m1281-1119.html

Glenn E. Campbell

HA Senior Historian

Comments