Lost And Found

- HistoricAnnapolis

- Apr 14, 2022

- 4 min read

Like every old city, Annapolis has suffered its share of devastating fires. In my last blog, I mentioned the 1704 blaze that destroyed Annapolis’s first State House.

Today, the Museum of Historic Annapolis at 99 Main Street occupies a building constructed after a 1790 fire wiped out a waterfront block on the south side of City Dock. Fire-cracked glass fragments recovered during archaeological excavations at the site are among the artifacts now on display in the new exhibition Annapolis: An American Story.

If not soon discovered and doused, a fire could quickly get out of control in a town largely built of wood. By law, colonial Annapolis homeowners and landlords were required to have buckets and ladders on hand to fight fires in their buildings. In 1755, the city imported an English fire engine to literally pump up the volume of water that could be brought to bear against any blaze.

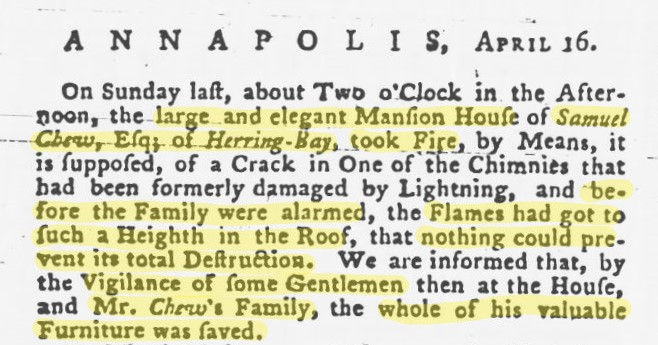

Fire also posed a serious threat to homes built in more rural, less densely populated areas. The April 16, 1772 Maryland Gazette reported the destruction by fire of a landmark residence overlooking Herring Bay, about 16 miles south of Annapolis.

The fire broke out in the “large and elegant Mansion House of Samuel Chew, Esq” at about 2pm on Sunday, April 12, presumably by way of “a Crack in One of the Chimnies that had been formerly damaged by Lightning.” The flames spread rapidly, reaching the roof before the occupants realized they were in danger. The inferno caused the “total Destruction” of the property, although Chew’s “valuable Furniture was saved” through the quick action of “some Gentlemen then at the House, and Mr. Chew’s Family.” Fortunately, there were no fatalities or serious injuries to report. Loss of the house was a personal tragedy for the Chew family, but it could have gone much, much worse.

Samuel Chew was the brother of Mary Chew Paca of Annapolis and the latest in a long line of men who shared the same name. One or more of those ancestral Samuel Chews built the house at some point between the mid-1690s and about 1720. After its destruction in April 1772, memories of the grand home faded from living knowledge, and physical evidence of its former existence was buried from view and swallowed by time.

That’s where the archaeologists of Anne Arundel County’s Lost Towns Project enter the picture. After searching for and discovering the “lost” colonial town of Herrington in 2001-04, the team shifted its attention to finding remnants of the nearby Chew mansion. Although the house was depicted on a 1732 map of the area, its precise position eluded investigators until 2006, when archeologists John Kille and Shawn Sharpe hit upon the correct spot. Four subsequent years of excavation work uncovered the remains of Samuel Chew’s imposing residence.

Kille, Sharpe, and Al Luckenbach, founder and then-director of the Lost Towns Project, published an article detailing some of their discoveries at the Chew site in the March 2013 issue of Maryland Archeology. I’ve included a link to the article at the end of this blog and encourage you to read if for yourself, but here are a few of its highlights:

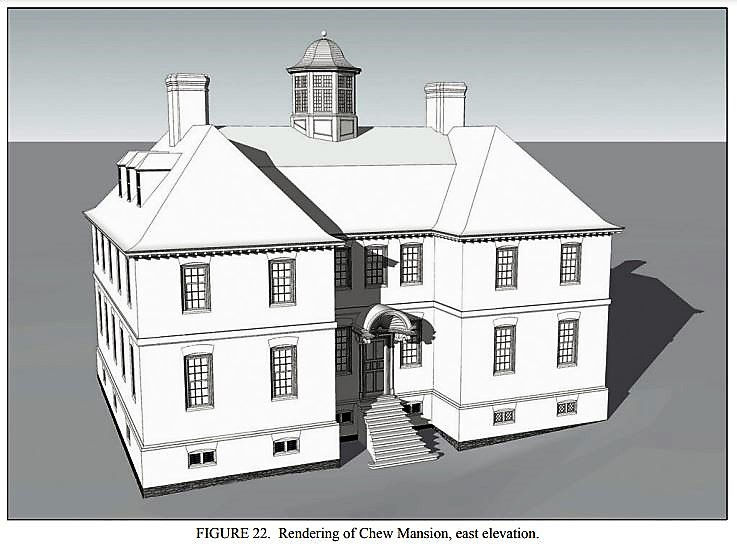

Samuel Chew’s house was “a highly elaborate, 66’ by 56’ masonry structure that was apparently the largest home in the Chesapeake region when it was built.”

With a full cellar and 2½ stories built to an H-shaped plan, the mansion’s floorspace was close to 14,800 square feet.

Architectural features included five types of molded bricks, an entrance floor of black and white stones presumably laid in a checkerboard pattern, molded plasterwork, and polychrome Delftware tiles decorated with variations on a flower pot motif.

Pools of melted window glass and burned ceramic fragments of both plain utilitarian and fine table wares testified to the destructive power of the 1772 fire.

The Lost Towns colleagues consulted with other experts, including fellow archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume and architectural historians Orlando Ridout V, Willie Graham, Cary Carson, Mark Wenger, Carl Lounsbury, and Ed Chappel. This collaboration led to the creation of a hypothetical 2-D first floor plan and conjectural 3-D computer rendering of the Chew house. Trey Tyler of RenderSphere in Richmond, Virginia produced the final 3-D image.

According to Luckenbach, Kille, and Sharpe, “At the time of [their home’s] construction the Chew family was at the very top of Maryland’s wealth scale. The structure they placed on a high ridge setting was clearly intended as a demonstration of this wealth, visible even to passing ships.… [F]or at least three generations, the Chew Mansion stood as one of the grandest architectural expressions in the Chesapeake. That this fact was virtually lost to human memory is a clear demonstration of archeology’s potential to add to our understanding of architectural history and to the lives these buildings represent.”

250 years ago, a devastating fire destroyed a remarkable South County home, but sometimes what seems to be lost can be found again.

You can read the April 16, 1772 issue of the Maryland Gazette beginning here: https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc4800/sc4872/001282/html/m1282-0086.html

Visit the Lost Towns Project’s website to read the March 2013 Maryland Archaeology article about the discovery and excavation of the Chew mansion site: http://www.losttownsproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Chew.pdf

Glenn E. Campbell

HA Senior Historian

Comments