Of Singular Advantage to this Country

- HistoricAnnapolis

- Jan 13, 2022

- 4 min read

By January 1772, the nonimportation associations of 1769 and 1770, which organized and enforced colonial boycotts of taxed English goods, were already a distant memory for many Americans. After all, Parliament had repealed most of the Townshend Duties back in March 1770, triggering a pent-up push to get back to business. True, the tea tax was still on the books, retained by Parliament as a face-saving assertion of its authority in colonial matters, but most merchants and consumers weren’t going to let that get in the way of resuming their pre-boycott trading and spending. In Annapolis and elsewhere, some patriot leaders had tried to hold the associations together, but they fell apart as 1770 came to a close. Now, more than a full year later, things were back to normal.

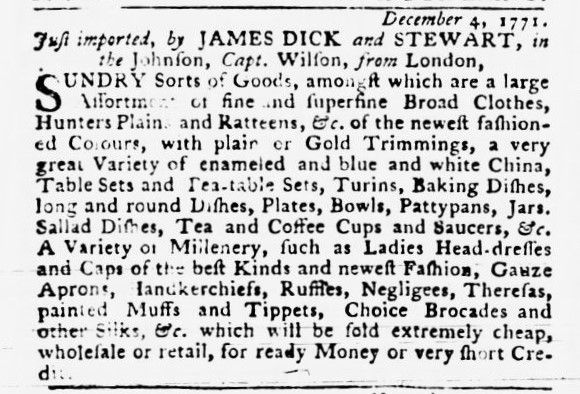

The Maryland Gazette issue of January 9, 1772 contained advertisements for several local businesses, including one placed by Annapolis and London Town merchants James Dick and Anthony Stewart. Dick and Stewart had been at the center of the Good Intent incident back in 1770 (see my blogs from April 2020), lambasted by county association inspectors for trying to import banned goods, but now they blithely advertised the recent arrival of all sorts of wonderful products, available now for purchase in their stores.

Dick and Stewart’s ad led with English fabrics: “fine and superfine Broad Clothes, Hunters Plains and Ratteens, &c. of the newest fashioned Colours, with plain or Gold Trimmings.” Table- and cookware followed: “enameled and blue and white China, Table Sets and Tea-table Sets, Turins, Baking Dishes, long and round Dishes, Plates, Bowls, Pattypans, Jars, Sallad Dishes, Tea and Coffee Cups and Saucers, &c.” Millinery goods rounded out the list: “Ladies Head-dresses and Caps of the best Kinds and newest Fashion, Gauze Aprons, Handkerchiefs, Ruffles, Negligees, Theresas, painted Muffs and Tippets, Choice Brocades and other Silks, &c.”

Another local merchant, William Rooke, advertised “a general Assortment of Goods…very cheap for Cash or short Credit,” starting off with a long list of fabrics ranging from calamancoes to crapes, damasks to denim, lawns to linen, and fustian to flannel. Rooke also had stockings, caps, purses, mitts, ribbons, gloves, shoe buckles, and stays in stock. Moving beyond clothing and personal accessories, he had “an Assortment of Stationery, Hard Ware, Ironmongery, Cutlery, Sadlery, Copper, Brass, Pewter, Tin, Stone and Glass Ware, &c. &c. &c.”

A lesser merchant might leave off at “&c. &c. &c.,” but not William Rooke! He finished his sales pitch with “Pitch and Tar, red and pickled Herrings by the Barrel, Soap and Candles by the Box, Jamaica old Spirits, West India and New England Rum, double and single Loaf Sugar, Muscovado ditto, Spices, fine Hynson Tea, fine Green and common ditto, and Bohea Tea.” As stated at the top of the ad, all of these goods were “just imported, in the Ship May, Captain McLachland, from London, and other Vessels from England.”

Annapolitans knew firsthand the advantages of living in a port town tapped into Great Britain’s impressive production capabilities and worldwide distribution network. As long as Parliament didn’t mess with the system by taxing American consumption of English goods, there was no reason for colonists to try their hands at manufacturing consumer products for themselves. Why go to the trouble and expense of learning how to make something like a quality woolen broadcloth when you could find yards of it at an affordable price at Dick and Stewart’s or another local store?

But what if Parliament did mess with the system again? They’d done it in 1765 with the Stamp Act and in 1767 with the Townshend Duties. Were American merchants and consumers always to be at the mercy of English politicians? Did they always have to rely on the fickle Mother Country for the necessities and luxuries of life? Could colonists strengthen their economic and political hands by getting into the manufacturing game themselves? Apparently someone in Pennsylvania thought so.

The January 9 Maryland Gazette reprinted a recent report out of Philadelphia, announcing that “On the First Day of January next, 1772, will be exhibited at the London Coffee-House, a Piece of Broadcloth, the Manufacture of this Province. As it is one of the finest and best perhaps ever made on the Continent, and as the Manufacturer has been at considerable Expence in procuring Engine Looms, &c. he hopes the generous Publick will encourage this infant Attempt. By this Specimen it will appear, that such Goods can be manufactured amongst us, and of singular Advantage to this Country.”

Philadelphia’s London Coffee-House stood at the southwest corner of what are now Front and Market Streets. Opened by entrepreneurial printer William Bradford in 1754, it was built with funding from more than 200 Philadelphia merchants and became their preferred gathering spot to talk business and make deals (some of which, as the image shows, involved the buying and selling of enslaved individuals). This was the perfect place for our unnamed upstart broadcloth exhibitor to find investors who could help him expand production and explore “other Branches which may be conveniently added.” Perhaps there was a profitable future in American manufacturing?

English fabric producers didn’t have anything to fear (yet!) from American competitors, but protecting Britain’s manufacturing dominance concerned some in Parliament. One little paragraph in the January 16, 1772 Maryland Gazette was so brief that it might be easily overlooked, but its content spoke volumes: “We are assured that a Bill for preventing the Migration of British Artificers to any foreign Kingdoms, or even the Colonies, which has been long in Agitation, will be brought in and passed the ensuing Session of Parliament.”

English politicians didn’t want a manufacturing brain drain to occur on their watch, and apparently they were preparing legislation that would keep their skilled craftsmen and inventors hard at work for the good of the Mother Country. All the more reason for Americans to encourage their own homegrown production efforts?

You can read the January 9 and 16, 1772 issues of the Maryland Gazette starting here: https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc4800/sc4872/001282/html/m1282-0006.html

Glenn E. Campbell

HA Senior Historian

#history #1772news #colonialhistory #marylandhistory #annapolishistory #annapolisnews #marylandgazette #importation #news

Comments